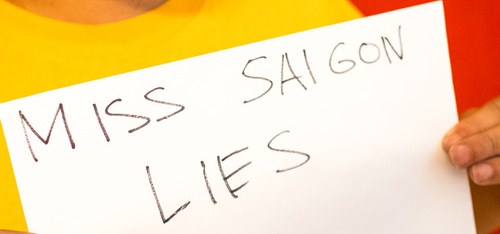

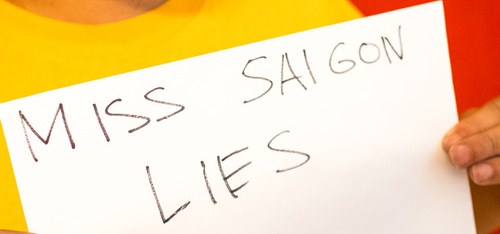

I don’t come out of my cave very often. Life’s kept me running too fast to pause for very long. However, when I heard that Miss Saigon was attempting to make a comeback, it infuriated me enough to come out of my shell. I thought to write a long essay/rant listing the many reasons why I hate this musical, but there are members of our community who are far more eloquent. Instead, I opted to add my voice to the many who are speaking their own truths on Don’t Buy Miss Saigon: Our Truth Project.

“A photo and story project to counter the racist, sexist, colonialist musical Miss Saigon, in our words and through our eyes. More info on dontbuymiss-saigon.com.”

18MillionRising is hosting a petition as well as more information about the campaign.

As a Vietnamese adoptee, an Asian woman and as a Vietnamese American, Miss Saigon scrapes across my still healing identity. Old memories leap into the present every time I see these tired, old stereotypes replayed.

“Me love you long time, little girl?” I was in fifth grade when a high school student chanted this at me on the school bus.

“You probably don’t want to know the truth. What if your mom was a prostitute?” said a family member.

While watching one of the many Vietnam War movies, cut to scene with prostitutes: “Hey, Sume, your mom’s on tv!” says my ex-SO.

“You’re should be grateful your dad saved you,” said another, “If he hadn’t, you would probably have ended up as a prostitute or dead.”

I could go on and on right up to the present, because this stereotype is so ingrained in the heads of American society that the assumption is almost second nature. The default excuse seems to be, “Well, there were prostitutes in Vietnam during the war.” Lame. That is a scenario that’s been played out in almost every country that’s had to deal with war.

As a young child, the stereotype was already being fed to me through movies, television and by my wonderful “white saviors” on a regular basis. When they wanted to “educate” me about “my people,” the lessons always somehow involved how lucky I was not to be among them. I slowly internalized the sense of shame and the indoctrination of self-hate/guilt/gratitude took root. Some actually meant well, however, none of them were aware or understood that I viewed the world through TRA eyes. Friends and family may have viewed “my people” as “the other,” but some part of me also saw myself as “other.”

My environment didn’t provide positive references to contradict all those negatives plus the ethnocentric, racist, stereotyped ideas were often packaged as cute, romanticized bundles which made them easier to digest. As a result, I built my identity around the way my environment viewed me which contradicted the way I was told to view myself. On one hand, I was “one of them” and expected to view myself as being the same as any other family member. On the other, I was suppose to be aware of my “lucky” status in being rescued from Vietnam and a people that promised nothing but prostitution and death.

In 2006, I wrote a piece for Nha Magazine which explains in more detail:

Stored in the very darkest corners of my mind is the picture of an embassy. A deflated American flag is being withdrawn from atop a flagpole. Scores of frantic men, women and children are crushed against the gates desperate to get out before the Viet Cong claim control of Saigon. Mothers are crying, holding their children high in the air amid the smells of smoke and diesel fuel pleading for someone to take them to safety. I hear the thumping of a helicopter over the cries of despair. It’s the sound of angel-wings beating hope into the air, promising salvation if they could just get past the gates.

I left Vietnam five years before the end of the war but those images have become like memories. Since early childhood, scenes similar to the chaotic evacuation sequence in Miss Saigon have been beaten into my brain by television, movies and photographs. For most of my life, Vietnam was a war, Saigon an evacuation, Tet an offensive, and I had escaped it all.

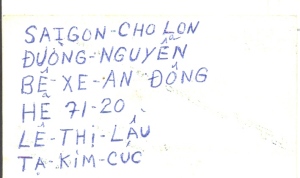

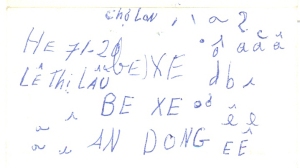

Born in 1970, my caretakers at Hoi Duc Anh orphanage in Saigon referred to me as Le Thi Buu Tran before my father adopted me. He had just completed his second tour as part of the American occupation. When my adoption process was complete, I had a new American name. Before I’d reached my first year, all traces of my Vietnamese heritage had been erased except for my adoption papers and my genetics. As my father boarded a plane destined for the U.S., I’m sure he envisioned new lives for us free of the country and the conflict we’d left behind. Years later, he would recall how I wailed the entire flight from Saigon to Honolulu.

My new home was a small town in East Texas where I would grow up the lone Asian for the next decade. The population of little more than a thousand was mostly white with smaller African and Mexican American minorities. A set of railroad tracks served as a loose dividing line between black and white while brown lived mostly on the rural outskirts of town. Though I lived on the “white side” of town, I was at the bottom of the racial hierarchy as the only Asian, the only Vietnamese.

Like most children, my world in the beginning was very small and rarely breached the safe boundaries of family. That would change when in 1975 which also marked the end of the war; I began my first year of school. My first clue that I was different from other kids was finding my green card in my mother’s purse. “Oh,” she replied matter of factly, “you’re adopted from Vietnam.” It meant nothing to me at the time but would later become a source of shame and embarrassment as I learned about Vietnam and its people through the eyes of post-war America.

“Gook! Go back to Vietnam!” I was still in elementary school when classmates first screamed those words. They held little meaning for me other than the obvious insult intended. Their true meaning was beyond my understanding. The majority of my access to Vietnam or anything “Asian” came through movies, television, history lessons in school, war documentaries and “war stories” told by those around me. Aside from stereotypical portrayals of Asians in the media, movies like Uncommon Valor and Full Metal Jacket only deepened my negative perception of myself. Unconsciously, I would harbor a sense of shame until my early thirties for my nationality as well as my race.

Unlike today, there were no culture camps or adoptee support groups to lift me from my isolation and instill knowledge of and pride in my birth country. Adoptees were considered as “blank slates” upon their adoptions and little if any importance was given to national, ethnic or familial origins. Given the environment in which I’d grown, I probably would have turned away from such opportunities even if they had been available. My need to blend into my surroundings took precedence over my longing to know. Such pursuits would have only reminded me that I was an ethnic chimera belonging nowhere.

Around the time I turned ten, another family adopted an older boy from Vietnam. I’d heard the news through the grapevine of my little town and wondered what he’d be like. It seemed fate might not be so cruel after all. I would no longer be the only one and perhaps he would be at the very least a friend, a doorway to my lost heritage at most. When he finally arrived, I could only stare at him fascinated from afar. Maybe I’d just grown too use to suppressing my loneliness, to closeting my curiosity or had been too concentrated on trying to assimilate and forget. The result was that we didn’t talk about either Vietnam, adoption or our experiences with racism and prejudice until almost twenty-seven years later. Our painful experiences closely paralleled yet we had suffered alone.

I eventually moved away to Bellevue, Nebraska which was a far cry from the tiny community in which I’d grown. It would be my first real interaction with people from the Asian community but I still found it difficult to relate. Being neither white nor feeling fully Asian, I felt no true sense of belonging even in such a diverse community. Shortly before my high school graduation, my family moved back to Texas where I would graduate and begin attending college. Having matured and feeling released from the social shallowness of high school, I began to seriously consider trying to make contact with other Vietnamese.

I was thrilled when approached by the representative of a Vietnamese student’s organization. “Are you Vietnamese?” he asked. “Yes,” I replied. “Do you speak Vietnamese?” was his next question to which I answered, “No, I was adopted.” He stared for a moment then smiled and said, “Thank you,” as he made a quick exit. I could do nothing but stare feeling as if I’d just been summarily rejected without reason. That moment would put an end to any thoughts of trying to reconnect to “my roots” for over a decade.

With the birth of each of my four children, the need to know grew until I could no longer ignore it. My childhood longing grew from a need to fill an emptiness left by my lost heritage and birth family. After my own children were born, filling in that vacuum became even more important in order to have something to pass onto my children. They had a right to know about Vietnam, its rich history and culture and to feel proud of that part of their heritage. Being such a later bloomer and already in my thirties added a sense of urgency.

I began researching through the library, newspapers and the internet looking for other adoptees and adoptee resources. At the same time, I started writing about my story and reaching out to others with similar experiences. It was surprising how much was actually out there. My desk became cluttered with books as I submerged myself in Vietnam’s history, vibrant culture and deep traditions. I revisited the war from other perspectives and learned about Vietnam through the eyes of its people. It was an overwhelming and sometimes painful experience. I felt like an amnesiac trying to reconnect to a family through old letters, photo albums and home movies. My journey back has only begun but by moving backwards, I’m also moving forward.

Saigon is no longer the abandoned city of my childhood. I am proud to claim it as my birthplace. Reaching beyond the narrow perspective that imprisoned me, Vietnam now is more than a war. Tet has become a special time to share what I’ve learned about Vietnamese food, culture and history with my children. Beyond that, I hope to pass down a deep commitment to family and pride in knowing who they are. I will probably never be able to fill in all the gaps or fully reconnect with the Vietnam of my past. That is gone, but I’ve come to realize that just as Vietnam begins to heal and move forward, so must I. The past is only part of the picture as I also come to terms with what it means to be a first-generation Vietnamese American.

So much for not writing a long essay/rant…